Recently, Wu Chi-Tsung was invited by Sean Kelly Gallery to shoot a short video named In the Studio. In this abstract yet frank video, Wu Chi-Tsung presents a poetic dance with one of his favorite materials – light. Employing long-exposures, he is visualising the battles and joys in search of inspiration as he follows the guidance of a beam of light in his once pitch-dark studio.

Let there be light. For Wu Chi-Tsung, light is the catalyst in his art, and time devoted in his darkroom allows beauty to gently appear. British video artist David Hall coined the term ‘time-based art’ in 1972, which refers to the art forms that require a certain amount of time to be fully revealed. While the concept was devised with traditional art forms such as paintings and sculptures in mind, and also emphasized the duration of time and the scale in space, Wu Chi-Tsung tends to interpret it in a reversed way. He deliberately uses time as a tool to blur the boundary between new media art and traditional art and to redefine moving and still images.

長時間曝光的風景,2004

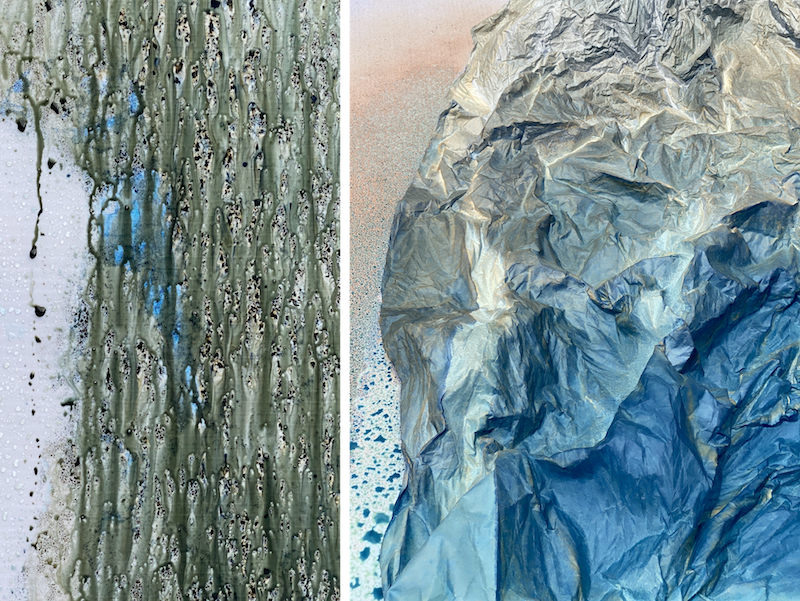

The necessity of long exposure is shared in most of Wu Chi-Tsung’s still works, such as the Cyano-Collage Series, the Wrinkled Texture Series, and the Long Time Exposed Landscape. Therefore, these works all contain a considerable scale of time and momentum. They have become a living fossil in which a complete time axis is fused together.

In Chinese, the phrase that represents a long period of time is Shiguang (時光), which is a combination of the words for Time (時) and Light (光). The considerable time that Wu Chi-Tsung spends battling with, adapting to, and coping with time and light is a key feature of his works. He tends to focus on simple techniques and daily objects, still he devotes himself to research time and light and applying his learnings to the original material and turning it into something completely different from, and even opposite to, commonplace perceptions.

宣紙在陽光下呈現出屋漏痕般的自然筆法

As one of the furthest-developed works so far, the Cyano-Collage Series demands a large amount of ‘exposed paper’ for paper-reading and collage. As hours of sunlight reacts with the cyanotype chemistry on the Xuan paper, the ordinary wrinkles on the paper transcend their physical features and gain a similar spiritual quality as in traditional ink painting. After this, the artist observes the textures and folds of every paper, to ‘read’ and contemplate them, and pick the ones that evoke and inspire the artist the most. For this precious ‘decisive moment’, which is almost one in a hundred, processing and storing paper have become a daily routine.

For his installation and video works that are more qualified to be called ‘time-based art’, time seems to be wasted or irrelevant. It moves forward, yet sometimes cycles; it goes by, yet sometimes stalls. As a reversed interpretation of time involving the artist’s understanding of Asian philosophies, these works have contributed to the complicity of the artist’s exploration of temporality. For instance, the Still Life Series, the Landscape in the Mist Series, and the Dust share a similar sense of stillness, in effect an almost nerdy gaze. Although these works last up to ten minutes, the visual message conveyed by the film tends to be relatively monolithic, as if they are a still frame stretched to fit a time axis. Nevertheless, it is exactly the seemingly meaningless gaze and the ostensibly wasted time that reveals the artist’s obsessed fascination and adamant aestheticism towards the object before the camera. Give it time.

2019年《灰塵》於德國威瑪藝術節展出現場

近日,吳季璁受尚凱利畫廊之邀,拍攝了短片《在工作室(In the Studio)》。這段抽象而坦誠的影像堪稱吳季璁與光共同呈現的雙人舞,他通過長時間曝光的技法將自己在創作中找尋靈感的過程具象化為獨自在漆黑的工作室中跟隨一線微光的指引摸索前進。

要有光。對於吳季璁而言,光是他創作中重要的催化劑,而時間則是他的暗房,令美徐徐浮現。1972年,英國錄像藝術家大衛˙霍爾(David Hall)提出「時基藝術」的概念,指需要經由時間才得以完整呈現的藝術形式,本義是與傳統的繪畫、雕塑等媒材相對照,強調作品在時間與空間維度的延展性。而在吳季璁的作品中,時間卻成為他主動混淆新媒體藝術與傳統藝術、動態與靜態的手段。

創作失敗的氰版相紙被從底板上刮去

《氰山集》系列、《皴法習作》系列、《長時間曝光的風景》等作品共通性地在創作中需要經歷長時間的曝光,令這些靜態作品從時間的積累中獲得了時間體量與內蘊的動勢。

在中文中代表較長一段時間的「時光」一詞由「時」與「光」結合而成,吳季璁與時間和光線之不可抗力相搏鬥、磨合與交融的漫長時光是其作品的重要內核。吳季璁的作品往往選擇最樸素的技法與最日常的媒材,把精力放在對於時間與光線的反復玩味與摸索上,令作品在這二者的共同作用下呈現出於原材料相異、更具想象空間的樣貌。

吳季璁於展覽現場調試《水晶城市》系列作品

《氰山集》系列作為吳季璁目前發展最充分的系列之一,需要儲備大量曬過的氰版相紙以供讀紙與拼貼。在光線的催化下,塗佈藥劑的宣紙上的平凡褶皺逐漸超脱物理性的范畴,而獲得了與歷來文人山水畫相通的精神屬性。其後,藝術家用類似於閱讀的方式去觀察曝曬過的紙張上呈現的紋理,從中挑選適合作品使用的紙張。為了這近乎百里挑一的「決定性瞬間」,處理、曝曬、儲存紙張成為了工作室每天日常工作的一部分。

相對而言,《小品》系列、《煙林圖》系列、《灰塵》等相對更符合「時基藝術」定義的作品則又以靜態的、發呆般的視角去凝視對象,是吳季璁對「時光」的反向思考。儘管作品時長拉到十分鐘左右,影片傳遞的視覺信息卻相對單一的,像是把一幀靜態圖像拉伸放入時間軸中。正是這樣的看似無意義的凝視與近乎浪費的時幅向觀者透露了藝術家對於鏡頭前的對象如醉如癡的眷戀之情。